Bivalve Bites: Oyster Aquaculture Research Roundup: Part II

BIVALVE BITES: EASILY DIGESTIBLE OYSTER AQUACULTURE NEWS

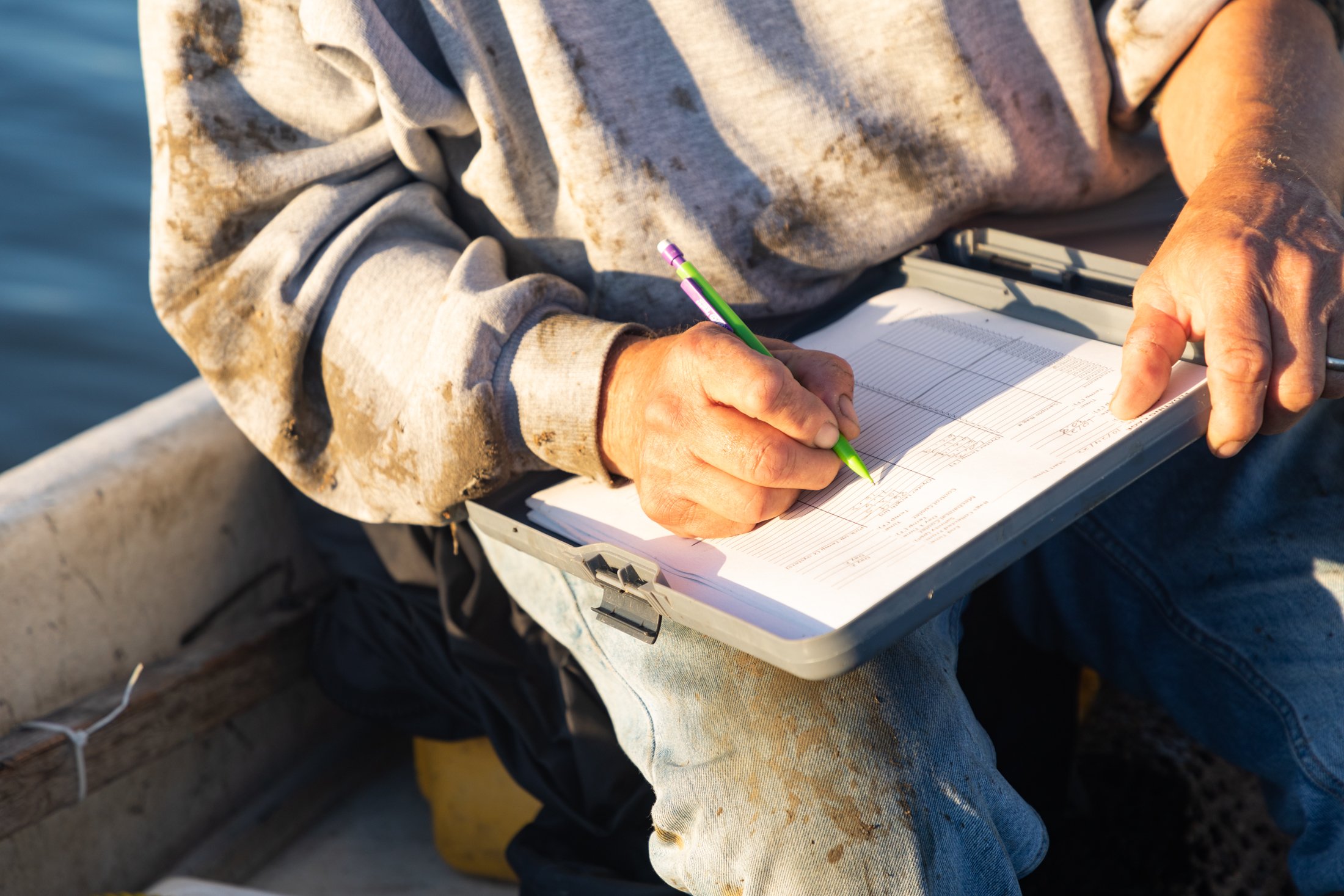

Vibrio sampling in Georgia. Photo by Shannon Wise

Last month, we brought you some short Q&As with a few applied researchers at Southern universities who are diving into the unknowns of oyster aquaculture to discover the information that can help our region’s oyster farmers better their practices, process and outcomes. (Read that article, here). We’ve got some more insight to share: Here’s what two more aquaculture scientists are currently studying and what they’re figuring out.

In Georgia

Tom Bliss, director of The University of Georgia’s Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant Shellfish Research Laboratory is on the team working to aid the State of Georgia in crafting the right regulations for its fledgling oyster farming industry.

Describe an oyster aquaculture research topic or project you’re currently involved with.

Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant Shellfish Research Laboratory (SRL) has completed collecting oysters over a five-month period (June-October) from floating cages and floating bags to determine the levels of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus in oysters. We are in the process of analyzing the data.

What are you and your team trying to learn with this research?

This research will help determine what the level of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus are in oysters at time of harvest (baseline) and following the two-hour time to temperature harvest method.

Why is it important to oyster aquaculture?

This research is important to aquaculture since Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio parahaemolyticus are natural bacteria in marine waters, and FDA requires a Vibro control plan for the harvest of shellfish. Current harvest rules in Georgia are for intertidal leases, which do not allow for the harvest of oysters when water temperature exceeds 81° F, since exposure to ambient air temperatures cannot be controlled. New regulations allow floating gear to be used on sub-tidal leases, that do not dry out at low tide, and data from this research will assist the state with development of a Vibro control plan for sub-tidal leases.

What are its potential impacts and benefits for oyster farmers and oyster eaters?

The potential impact from this research is that if Vibro levels are appropriate, a vibrio control plan to allow oysters to be harvested from sub-tidal leases can be developed. Currently, oysters are harvested only when water temperatures are below 81 F, typically October-May. This would allow for oysters to be harvested from June-September from sub-tidal leases.

In North Carolina

Ami Wilbur, director of The University of North Carolina Wilmington Shellfish Research Hatchery and Associate Professor, is working with a team across several higher ed institutions to understand mass oyster mortality events.

Describe an oyster aquaculture research topic or project you’re currently involved with.

With colleagues at NCSU (Tal Ben Horin), UNC-CH (Rachel Noble), and VIMS (Corinne Audemard, Jessica Small and Kim Reece), I am investigating the causes of spring mortality events in cultured oysters with support from the NC Commercial Fishing Fund.

What are you and your team trying to determine or learn with this research?

These events can be catastrophic (exceeding 85 percent) and are not associated with any known oyster pathogens. We are exploring the potential variability in susceptibility of different lines and ploidies, and site effects, in an effort to establish strategies for developing resilient lines. Environmental, microbial and metabolomic sampling will identify testable hypotheses as to the potential cause(s) of these mortality events.

Why is it important to oyster aquaculture?

Resilient lines are critical to the ongoing and future success of oyster aquaculture.

What are its potential impacts and benefits for oyster farmers and oyster eaters?

These mortality events threaten not only the expansion but also the sustainability of oyster farming in the areas that experience the events. Fewer oyster farms can lead to a reduced supply of oysters for consumption.